Spellbinding space opera adventure

High-octane science fiction full of intrepid starfighters, lovable bots and terrifying aliens. Read M.G. Herron!

Start your next series

1

/

of

3

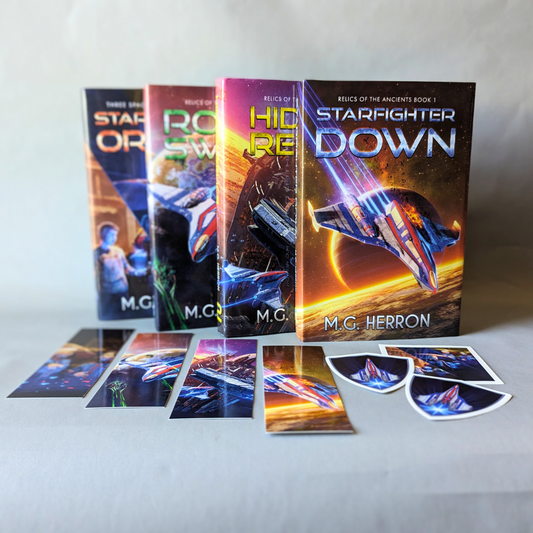

Bundle books and save

Save big on M.G. Herron's book bundles! Only available here.

-

Relics of the Ancients: Exclusive E-book Bundle

Regular price $19.99Regular priceUnit price / per$38.94Sale price $19.99Sale -

Relics of the Ancients: Exclusive Audiobook Bundle

Regular price $29.99Regular priceUnit price / per$85.94Sale price $29.99Sale -

Relics of the Ancients: Exclusive Digital Bundle

Regular price $45.99Regular priceUnit price / per$124.94Sale price $45.99Sale -

Relics of the Ancients: Exclusive Paperback Bundle

Regular price $64.99Regular priceUnit price / per$99.96Sale price $64.99Sale -

Relics of the Ancients: Exclusive Signed Hardback Bundle

Regular price $119.99Regular priceUnit price / per$179.96Sale price $119.99Sale

1

/

of

5

Who is M.G. Herron?

M.G. Herron is the author of more than 10 bestselling sci-fi adventure novels. He gets up every morning excited to tell stories full of space travel, lovable bots, alien civilizations, and ancient mysteries. MG (also known as Matt) writes from Austin, TX, where he lives with his patient family and loyal canine sidekick.

What readers are saying...

-

Starfighter Down is “excellent Sci-Fi, action-packed, and spellbinding.”

–R. Adkins, Kindle reader

-

Culture Shock is “a fast moving SF joy ride.”

–The Mysterious Amazon Customer, Kindle reader

-

M.G Herron is “a real original story teller.”

–Anonymous, Goodreads reader

Relics of the Ancients

Unveil the ancient past. Defend humanity's future.

-

Book 1: Starfighter Down

Regular price $5.99Regular priceUnit price / per$7.99Sale price $5.99Sale -

Book 2: Hidden Relics

Regular price $7.99Regular priceUnit price / per -

Book 3: Rogue Swarm

Regular price $7.99Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sale

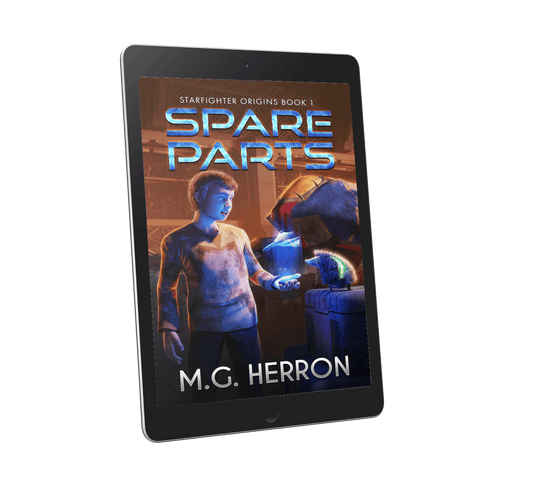

SaleBook 1: Spare Parts

Regular price $3.99Regular priceUnit price / per$4.99Sale price $3.99Sale -

Book 2: Raptor

Regular price $4.99Regular priceUnit price / per -

Book 3: Operation Heartstrike

Regular price $4.99Regular priceUnit price / per -

Books 1-3: Starfighter Origins

Regular price $7.99Regular priceUnit price / per

1

/

of

7

Translocator Trilogy

Where high-tech disaster meets ancient Mayans. A complete portal fiction trilogy!

-

Book 1: The Auriga Project

Regular price $3.99Regular priceUnit price / per$4.99Sale price $3.99Sale -

Book 2: The Alien Element

Regular price $6.99Regular priceUnit price / per -

Book 3: The Ares Initiative

Regular price $6.99Regular priceUnit price / per -

Books 1-3: The Translocator Trilogy

Regular price $9.99Regular priceUnit price / per

1

/

of

4

Browse books by format

-

-

-

Paperbacks

Browse PaperbacksFor those who just love the vanilla scent and comforting feel of a paperback novel.